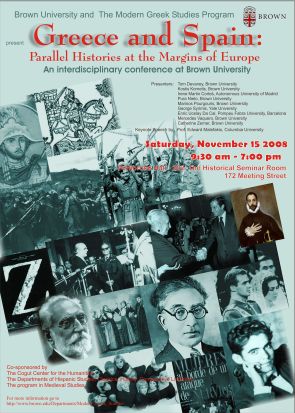

Ένα πάρα πολύ ενδιαφέρον συνέδριο έγινε στις 15 Νοεμβρίου 2008 στο Πανεπιστήμιο Brown των ΗΠΑ. Σας παραθέτουμε εδώ την αφίσα και το πρόγραμμα που μας έστειλαν από το πανεπιστήμιο.

(κάντε κλικ για μεγαλύτερο μέγεθος)

The Reasoning behind the Conference

Three decades ago the term Southern Europe was beginning to enter the academic vocabulary. Its point of departure was the suggestion that there existed striking similarities between mainly Portugal, Spain, Italy and Greece; economic backwardness, social divisions, political instability and similar patterns of behavior were but a few of the common factors that linked them together. The almost simultaneous collapse of the dictatorships in Portugal, Greece and Spain in the mid-1970s, the transition to and consolidation of democracy and the move towards the European norm confirmed the usefulness of this term as a coherent unit of analysis. In search of the parallel histories and the often unexpected connections that shed light on cross-national phenomena, this project aims to break down the above quartet and focus on two of its components: the two opposite poles - Greece and Spain. The reason for this, is that contextualization becomes less abstract and more convincing if the number of units compared decreases, to paraphrase Heinz-Gerhard Haupt.

The aim of this conference is to seek a deeper understanding of the analogies, common patterns and converging elements between Greece and Spain, in contrast to current academic trends which argue for the paramount importance of national particularities and cultural exceptionalisms. Our goal is to critically address stereotypes and question the generalizations and certainties of national historiographies, in order to ‘render the invisible visible’. By engaging scholars from different departments and disciplines we further aim to increase the interdisciplinary ties within the University and to provide a model for a comparative, or rather, cross-national historical approach that covers an extended chronotopical area. Rather than a strict comparison between nations, societies, political or economic structures, this project could rather be termed histoire croisée, as it tries to go beyond fixed units.

In this framework, the conference project seeks to understand not only the social conditions that brought about democratic reforms, fascist reactions or peasant revolutions in the two countries. It also aims to break down the convention that wants comparison to be made exclusively in the field of contemporary history rather than in medieval or early modern history, as well as attempting to compare time periods as well as geographic units. This longue–durée approach suggests that a comparison will be useful beyond the nation-state structure of the contemporary period, in times in which national consciousness was more fluid than consolidated. Starting from the middle ages, the project sets out to surpass the imaginary line between the Byzantine world and its western counterparts, arguing for cultural transfers and common developments ever since the 13th century, despite cultural and socio-political barriers.

Accordingly, the first component, the medieval one, deals with the contact zones between the Spanish and Byzantine worlds. What are the common denominators between the epic poetry of the Middle Ages, including the depiction of the legendary figures of Dhighenis Akritas and El Cid, who were famously fending off alien invaders? What was the effect of the Almogavar invasion of Greece in the 14th century and what is the legacy of the Catalan presence in Athens? 1492 is a key year, since it marks the expulsion of the Spanish Sephardim Jews, a great number of whom found refuge in Salonica. The interaction between the Spanish past and the Ottoman present, as well as the itinerary of this powerful community throughout the centuries is of particular interest, especially with regard to its political, social and cultural aspects. The massive deportation and annihilation of the Sephardic Jews of Salonica by the Nazis during WW II (1943) and the role the Spanish state in granting them passports to freedom is another issue that requires attention.

A key figure connecting the two peninsulas is of course Domenicos Theotokopoulos, more widely known as “El Greco”. As part of the attempt to place him within a wider historical context we seek to look into issues pertaining to the nature of the channels of communication between the Cretan Renaissance and the Spanish “Golden Age” as well as to the type of networks which operated throughout the Mediterranean sea, connecting its opposite poles in the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries. The emergence of the modern era and the creation of the Modern Greek State brings us to the issue of the reception of Spanish literature in Greece and vice versa, including the publication and critical reading of classical texts. In particular, what was the impact of the “irreverent” Emmanuel Roidis or Nikos Kazantzakis on Catholic Spain, and later on, what was the impact of Federico Garcia Lorca on inter-war Greece? What can be said about the translation and reception of literary works in the respective countries?

In political terms, the almost synchronic authoritarian turn of the two countries in 1936 invites further comparisons. What were the similarities and differences between the Spanish and Greek civil wars and their aftermaths? Issues of political violence, state repression and censorship are of great interest, starting with Metaxas and coming to a head with the Greek Colonels in 1967 – a fact that brought Greece closer to Spain “spiritually”, according to Franco’s right-hand man Admiral Carrero Blanco. The similar ways in which the two regimes tried to ‘liberalize’ from within, the role of the exiled Communist Parties as well as the reaction of the civil society and especially the students, invite yet another comparison. What was the role and mutual influence of cinema, theatre and literature and what were the common points of reference in terms of defiance, including cross-references such as Panagoulis and La Pasionaria, Saura and Gavras? What was the stance of the Orthodox compared to the Catholic Church? Finally, the two countries’ transition to democracy in the 1970s, the emergence of socialist governments and their European integration in the early 1980s constitute another common trajectory that invites comparison.

By seeking to trace common denominators in the Greek and Spanish thought, literature and history, this conference will aim to contribute to the deepening of the research on the two countries on a comparative level. By analyzing their similarities and differences it sets out to enhance not only the understanding of the two countries’ distinct and asymmetric developments but of the macro-historical evolution of the entire Mediterranean area.

Sellected Bibliography

- Filippis Dimitris E., 1936. Greece and Spain, Athens 2007.

- Green Nancy L., ‘Forms of Comparison’ in Deborah Cohen & Maura O’Connor (eds), Comparison and History. Europe in cross-national perspective, New York & London 2004, Haupt Heinz-Gerhard, ‘Comparative history – A contested method’, in Historisk Tidskrift, 2007,127, 4, 697-716.

- Kalyvas Stathis, ‘How not to Compare Civil Wars: Greece and Spain’, in Martin Baumeister & Stefanie Schüler-Springorum (eds.), The Spanish Civil War in the Age of Total War. Chicago, 2008 (forthcoming).

- Malefakis Edward, Southern Europe in the 19th and 20th Centuries: An Historical Overview, 41-56.Working Paper, Instituto Juan March, 1992/35, January 1992.

- Werner Michael & Zimmermann Bénédicte, Beyond Comparison: Histoire croisée and the challenge of reflexivity, in History and Theory 45 (1), 30–50.